Part I: When insufficient disclosure becomes a case (1)

In this new section of our blog, we want to deal with the pitfalls that cause patent applications to fail again and again without need. The main focus will be on current decisions of the EPO and the German Federal Court of Justice (BGH), which we also want to explain to non-experts.

Introduction

Most patent applicants are familiar with the fact that their invention must be new, inventive and industrially applicable. What is less well known is that the secondary requirements for patentability also include that the claims are clearly formulated (Art. 84 EPC) and that the invention is sufficiently disclosed (Art. 83 EPC). In this blog, we will look at the disclosure issue.

The reasoning behind this requirement lies in the deal that the patent applicant and the public make with each other: In return for informing the public about his invention and thus giving them the opportunity to develop it further, the applicant receives a monopoly for a limited period of time and territory, namely a patent. This enables him to prohibit unauthorized third parties from using his invention. However, this presupposes that the invention is also disclosed so comprehensively that the relevant skilled person is in a position to put the technical teaching offered into practice without having to become inventive again himself. While case law generally considers a certain degree of experimental optimization to be reasonable, the aim is to avoid the skilled person first having to set up an extensive research program in order to distil the actual technical teaching from the disclosure offered in the patent application. Keeping this is mind, different issues need to be addressed:

„One way“ or „Only one way“?

In practice, the requirement of Art. 83 EPC regularly leads to the question of up to what point one can still speak of a sufficient disclosure (synonym: enablement) and when this is no longer the case. In this context, it is often stated that it is allegedly sufficient if at least exactly one solution is shown. However, current case law shows that this generalization falls short of the mark.

The two recent decisions T 149/21 (2) und T 867/21 (3), both from 2023, point the way forward here. According to these decisions, the identification of exactly one way of achieving sufficiency in disclosure is a necessary but not always a decisive criterion. For example, if the technical teaching comprises more than one embodiment, feasibility over the entire scope of the claim is only given if either

(a) a separate solution is also disclosed for each of these embodiments or

(b) the person skilled in the art is able to understand the disclosed technical teaching in a simple manner on the basis of his expert knowhow in such a way that the non-disclosed embodiments are accessible to him without any inventive intervention.

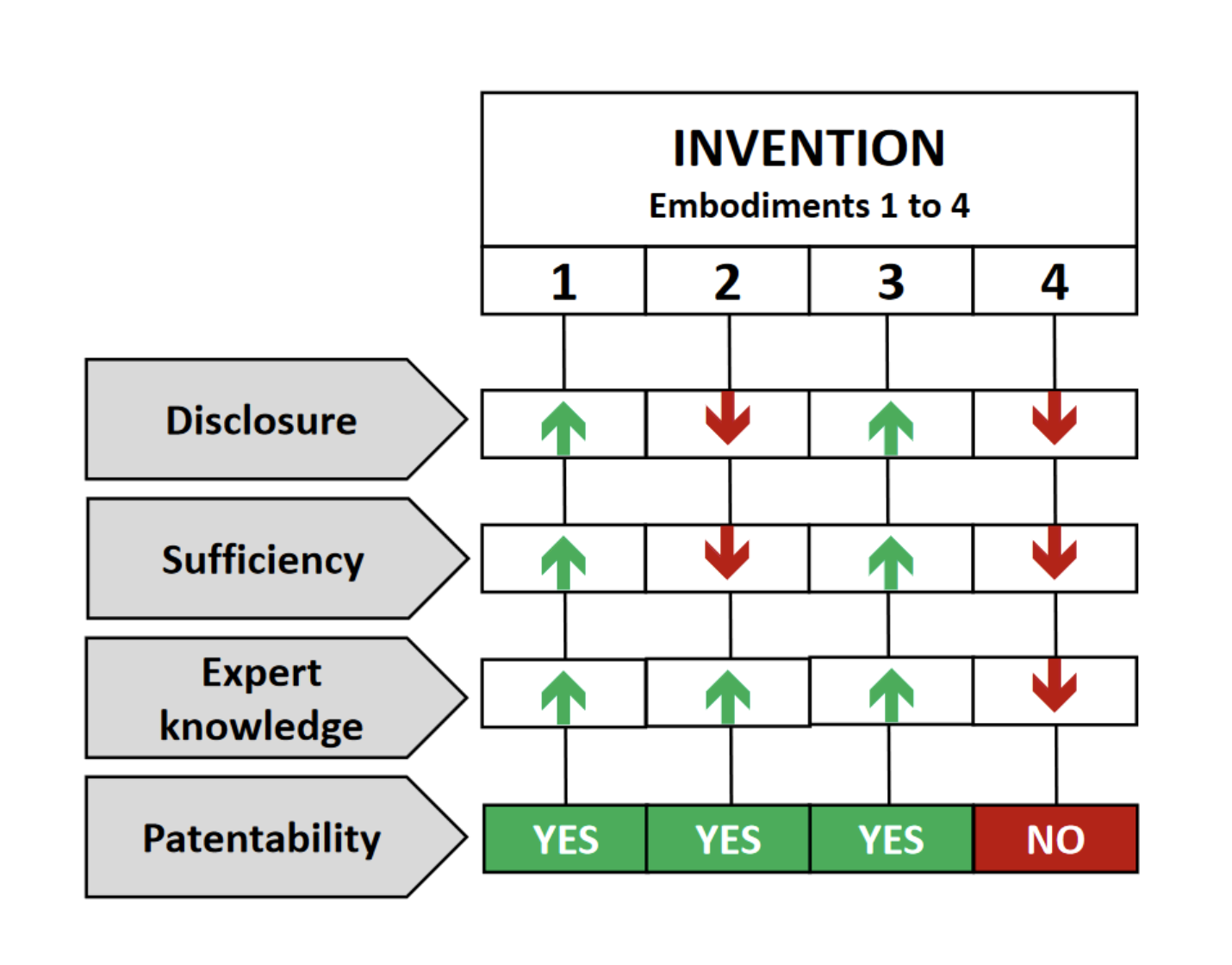

This is shown schematically in the following figure:

The invention comprises four embodiments, of which, however, only for alternatives 1 and 3 are ways of practicability indicated. Although there is no disclosure for alternative 2, this deficiency can be remedied by the person skilled in the art using his knowledge. For embodiment 4, this exception is also out of the question. In the end, embodiments 1 to 3 are thus sufficiently disclosed. This means that the claims can only be granted to the extent of these three alternatives. If it only becomes apparent after the patent has been granted that individual embodiments are not sufficiently disclosed, the patent can be revoked or limited in opposition proceedings, as the lack of disclosure under Art. 83 EPC also constitutes an independent ground for opposition.

It should be noted that any deficiency in disclosure cannot be cured either in examination or opposition proceedings by the subsequent submission of documents, for example comparative tests. Once this deficiency exists: game over!

Toxic and exotic embodiments

Anyone who has experience of proceedings before the EPO knows that the practicability of an invention is often disputed by the examiner citing embodiments which, although they can be formally encompassed by the claims, are not practicable at first glance. A typical example is the indication of concentration ranges in a mixture which do not complement each other 100%, depending on how the lower and upper limits for the components are combined. Even the indication that the claims are subject to the proviso that the quantities must be 100% complementary is often not sufficient to prevent an objection under Art. 83 EPC. The practical tip here is to expressly mention that purely mathematical embodiments which do not add up to 100% are not claimed and that the skilled person is able to find such embodiments which fulfill the teaching without having to take inventive step on the basis of the overall disclosure of the application.

But what about technically impossible embodiments that are not readily apparent in advance? Surprisingly, the EPO applies different standards when assessing such cases. The Boards of Appeal for Mechanics allow the skilled person to immediately recognize and mentally exclude such embodiments on the basis of his technical knowledge; the practicability of the overall teaching is therefore not impaired (4).

For the fields of chemistry and pharmacy, on the other hand, it is assumed that it is decisive here that an effect associated with a numerical range, for example, is plausibly demonstrated over the entire claimed range. Incidentally, this view was also taken by a Board of Appeal in the field of mechanics, which, however, was silent on the reasons why this argument does not apply to mechanical inventions.

Does this mean that there is a higher burden of proof for inventions in the fields of chemistry and pharmacy? It would be nice if this could be answered unambiguously, but the EPO is Janus-faced in its decisions on this subject. The following assessment therefore reflects a tendency rather than being truly fact-based. However, if one consults the aforementioned decisions T 149/21 and T 867/21, then an applicant may in principle rely on the fact that not every conceivable, yet obviously meaningless embodiment renders a claim insufficiently disclosed. Rather, the claim must be considered from the point of view of a person skilled in the art, which means that only those embodiments which prove to be technically meaningful are to be taken into account. Embodiments that are described as „toxic“ or „exotic“ in the wording of the decisions should therefore be excluded from the question of disclosure, as should alternatives that are not technically feasible even at first glance.

Size still matters

The question of whether an invention is practicable or not is often answered in the negative with the argument that the scope of the claim is far too broad. Therefore, it cannot reasonably be assumed that the invention is practicable over the entire breadth of the claim. The argument is also often presented as an objection to inventive step under Art. 56 EPC; however, the consequences are the same.

It should be noted here that an examiner examines a patent application in accordance with the guidelines and does not act as an expert on its technical suitability. The burden of presentation and proof for practicability therefore lies with the EPO or the opponent. Only if there are doubts that can be verified and confirmed by facts – e.g., by submitting documents from the state of the art – this objection can take effect, as set out in the landmark decision T 500/20 (5) The examiner’s „feelings“ plays no role here.

However, applicants should not make things quite too easy for themselves. In a whole series of decisions, the Boards of Appeal have established the principle according to which the scope of the claims and the overall disclosure must correlate. If a broad claim is novel and inventive in the light of the prior art, it is nevertheless only allowable if the application also contains a disclosure that is broad enough to reflect this scope. In reverse, a claim may be considered novel and sufficiently disclosed, but not inventive, in case the disclosure does not enable the expert to execute the teaching over the full scope without becoming himself inventive (6). This is again intended to prevent the skilled person from having to extract the embodiments which actually show the technical effect from a very broad teaching.

Practical tips for applicants

– If a technical teaching contains several embodiments, a way of carrying out the technical teaching must be disclosed for each of these embodiments;

– This does not apply to embodiments which are immediately recognizable by a person skilled in the art as technically impossible or senseless, or the implementation of which the expert can deduct from his general technical knowledge;

– In the case sufficiency of disclosure or lack of enablement is contested, the burden of proof generally lies with the Office or the opponent;

– The broader the claimed scope of protection, the more detailed the description and examples must be to support it.

– A lack of disclosure existing from the beginning cannot be remedied in retrospective!

(1) Vgl. BOSTEDT et al. GRUR Patent 7/2023, p280-285

(2) GRUR-RS 2023, 23938

(3) GRUR-RS 2023, 27809

(4) T 2773/18-3.2.04 GRUR-RS 2021, 16688

(5) GRUR-RS 2023, 2274

(6) T 939/92, ABl 1996, 309; T 694/92 ABl. 1997,408; T 583/93, ABl. 1996, 496